The COVID-19 pandemic set in motion many new ways of living, working, and learning. Some of these trends—such as online shopping—have levelled off over recent months, but one thing is for sure: online learning is not only here to stay but has become a critical new standard for student education and employee up-skilling.

With such a rapid rise in online learning, it’s easy to miss best practices, jump to quick solutions, and expect that all online learning technology is mature enough to deliver the best learning outcomes to your course participants.

Importantly, with a new standard of learning comes a series of new best practices. Learning experiences can be improved through online course models, but not without a standard of practice to address common challenges and fulfill the promise of online and hybrid learning.

Let’s explore what you need to know about online learning in 2022 and beyond from over a decade of research through to the latest findings.

First, let’s talk about learning models

Did you know that 15-20% of the world’s population is neurodivergent?

Neurodiversity refers to the concept that not everyone’s brain functions in the same way. People who are neurodivergent think, learn, and process information differently than neurotypical individuals. This includes a diverse range of neurological, neurodevelopmental, and learning differences, including specific disabilities such as autism, ADHD, and dyslexia.

Students and employees, no matter if they are neurodivergent or neurotypical, benefit from having choice as to how and when they engage with course content. In addition to considerations around neurodiversity, there are accessibility considerations, such as language, motor skills, hearing and sight disabilities, and more.

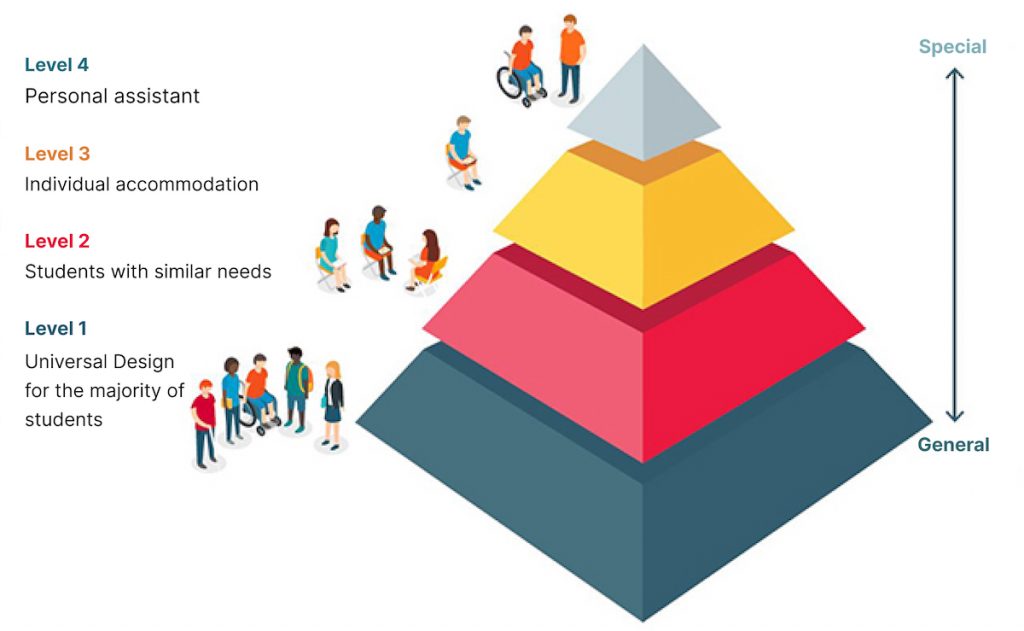

Educators use the term differentiated learning to describe teaching in a way that is flexible to a variety of learner needs and preferences, rather than a single type of lesson or assignment given to an entire group of learners. Differentiated learning is moving towards becoming standard practice in many K-12 education spaces and will be the next critical area of focus for employee upskilling.

Historically, educational programs and course models have not supported flexible learning options or provided accommodations for people with disabilities—preferring to offer a one-track path for course participants. Expanding this one track path to offer choice to learners is critical to learning program success. That’s where learning models such as Universal Design for Learning (UDL) bring intention to course planning and understanding of how different learners can be supported along their learning journey.

Importantly, technology can enable the most accessible, flexible, and effective content for all learners, but it’s essential to understand how to realize these benefits.

Let’s look at the research that’s identified practices that elevate online learning

Between the wealth of research that has been conducted over the past decade, along with our ongoing education and training work, we can quantify key impacts on learners. Highlights include:

- Accessibility and the impact of online education on learners with disabilities

- Learners prefer online learning

- Bringing human interaction to online learning

- Establishing an online course model

Let’s unpack each of these.

1. Accessibility and the impact of online education on learners with disabilities

Learners with disabilities often lack support to succeed in online education. This includes a lack of access to accommodations and appropriate services such as an individual education plan (IEP), audio-supported reading, specialized instructions, and affordable education.

Considering models for removing these barriers, accommodating multiple modes of content, and making online courses more accessible helps to establish an equitable, inclusive, and accessible learning environment that fosters success.

Over 95% of websites have basic accessibility issues. Online courses are no different, but this doesn’t have to be the case.

While there are standards-based approaches to enabling online learning to be accessible to all, it is not a common practice. Not all technology platforms, or Learning Management Systems (LMS), support these best practices. Bringing web accessibility standards to online learning is becoming an industry-wide priority and the next step to ensuring your organization’s success by welcoming all learners to fully participate in learning activities.

2. Learners prefer online learning

Virtual learning has consistently led to increased learner satisfaction.

Learners have benefitted from online learning when they have the flexibility and convenience of completing courses at their own pace and time, with the ability to reinforce learning through repetition that comes with continued course access.

Online courses enable new modes of interaction while offering varied ways of engaging with course content that can radically improve overall course engagement and learning outcomes.

But there are challenges.

Addressing the challenges of online learning

Online learning continues to present unique challenges for learners regarding access to support, self-motivated engagement, course delivery speed, and self-regulated learning.

3. Bringing human interaction to online learning

Historically, human contact and interactions have been limited with online courses. We now know that enabling instructor-learner interactions and communities of practice are critical to keeping learners engaged and encouraged to learn.

Education is inhibited when learners don’t have anyone to ask for help.

Providing online learners with access to instructors, real-time and ongoing feedback, and communities of practice, fulfills the promise of online and hybrid learning to improve learning outcomes over strictly in-class courses.

4. Establishing an online course model

When virtual courses lack structure, learners tend to lose motivation and interest in completing them. Compared to traditional face-to-face courses, the dropout rates for online courses are 20% higher. Furthermore, learning management systems (LMS) can be lacking in collaborative spaces. This can hinder real-time collaboration as online learners may not have the same opportunities to learn or work together with peers unless educators design courses specifically with human interaction in mind.

Furthermore, in-class courses do not directly translate to online delivery. It’s critical to be mindful of the opportunities online affords to improve engagement and interaction, support self-directed learning, and offer modes of learning that serve all learners, in order to design courses that leverage these benefits.

Ultimately, online course structures and models can better facilitate multiple learning models, including learning at a student’s own pace and being able to engage through written, oral, and other means that work best for them. Providing different interactions to increase learner engagement, facilitating teacher and peer support and dialogue, and providing self-regulated learning (SRL) support and collaborative learning communities are critical considerations in your online course planning.

How can online learning best serve all learners?

With intention comes results. The research is clear: online learning provides the best model to serve all users.

You can grow course engagement, improve learning outcomes, and reach more learners by ensuring multiple modes of learning, access to courses, bringing a human connection, and following standards of practice in delivering courses.

Whether you’re just getting started, or have been serving learners online for years, we can help you deliver improved course outcomes.

Our approach and standards-based technology provide a more usable, accessible, and inclusive experience for all.

Leverage features and capabilities that support diverse learners, including self-directed learning, captions and transcripts, a diverse suite of interactions, and screen reader support, all of which follow standards that enable integration with common LMSs.

Our platform removes barriers to accessibility by providing different modes of content access and engagement, including mouse, touch, keyboard, voice, screen reader, and zooming across multiple screen sizes and devices.

Our expertise will help you complete the transition from limited in-person learning to leveraging online and hybrid learning to improve enrolment, satisfaction, and learning outcomes.

We support established instructional design teams and new learning and training initiatives.

References

Aragon, S. R., & Johnson, E. S. (2008). Factors influencing completion and Noncompletion of Community College Online Courses. American Journal of Distance Education, 22(3), 146–158. doi: 10.1080/08923640802239962

Baber, H. (2020). Determinants of students’ perceived learning outcome and satisfaction in online learning during the pandemic of covid19. Journal of Education and e-Learning Research, 7(3), 285–292. https://doi.org/10.20448/journal.509.2020.73.285.292

Basham, J.D., Stahl, S., Ortiz, K., Rice, M.F., & Smith, S. (2015). Equity Matters: Digital & Online Learning for Students with Disabilities. Lawrence, KS: Center on Online Learning and Students with Disabilities.

Hu. M & Li. H. (2017). Student Engagement in Online Learning: A Review. 2017 International Symposium on Educational Technology (ISET), 39-43. doi: 10.1109/ISET.2017.17.

Leong, P. (2011). Role of Social presence and Cognitive Absorption in Online Learning Environments. Distance Education, 32 (1), 5-28. doi: 10.1080/01587919.2011.565495

Lin H. F. (2007). Measuring Online Learning Systems Success: Applying the Updated DeLone and McLean Model. Cyberpsychology & Behavior: 10 (6), 817–820. https://doi.org/10.1089/cpb.2007.9948

Neurodiversity. National Cancer Institute. (2022).

https://dceg.cancer.gov/about/diversity-inclusion/inclusivity-minute/2022/neurodiversity

Nguyen, Tuan. (2015). The Effectiveness of Online Learning: Beyond No Significant Difference and Future Horizons. MERLOT The Journal of Online Teaching and Learning. 11. 309-319.

Sim, S., Sim, H., & Quah, C. (2021). Online Learning: A Post Covid-19 Alternative Pedagogy For University Students. Asian Journal Of University Education, 16(4), 137. doi: 10.24191/ajue.v16i4.11963

Sit, J. W. H., Chung, J. W. Y., Chow, M. C. M., & Wong, T. K. S. (2005). Experiences of online learning: Students’ perspective. Nurse Education Today, 25(2), 140–147. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.nedt.2004.11.004

Wong, J., Baars, M., Davis, D., Van Der Zee, T., Houben, G., & Paas, F. (2018). Supporting Self-Regulated Learning in Online Learning Environments and MOOCs: A Systematic Review. International Journal Of Human-Computer Interaction, 35 (4-5), 356-373. doi:10.1080/10447318.2018.1543084